Chidakash Kalalaya celebrated Bhanotsav -a ‘meagre-modes’ of Indian drama. Padma Prabitakam -The lotus consent -written by Sudraka was the first day’s fare.

Artistic Director Piyal Bhattacharya’s work had the blessings of drama stalwart Ratan Thiyam, who graced the two-day long festival, celebrated at Padatik Little Theatre, Calcutta. Ratan Thiyam welcomed the young Artistic Director and his understanding of his subject per se, which was a valuable validation for the rising dramatist with a very special mission. Dr. Piyal Bhattacharya is dedicated and determined to preserve, practice and propagate India’s cultural heritage through Guru-Sishya -Parampara. It has been his endeavour to research and works extensively with Bharata’s Natya Shastra to bring about a form of practice named Marga Natya. This pioneering movement was started by him in 2013.

‘Bhaanak’ and ‘Bhaanika’ was presented according to Natyshastraic instruction as codified by Bharata muni in Natyashastra.

In the presentation of Natya, the choreographer has resorted to the use of Uparupaka-abstract dance poetry- in a reconstructed form, to express their desired message.

Uparupaka was specially chosen because it gave ample room for re-construction by the Acharyas to make changes while remaining rooted to the Shastras.

Bhaanak and Bhaanika primarily focused on the manifestation of Bhava and Rasabhinaya.

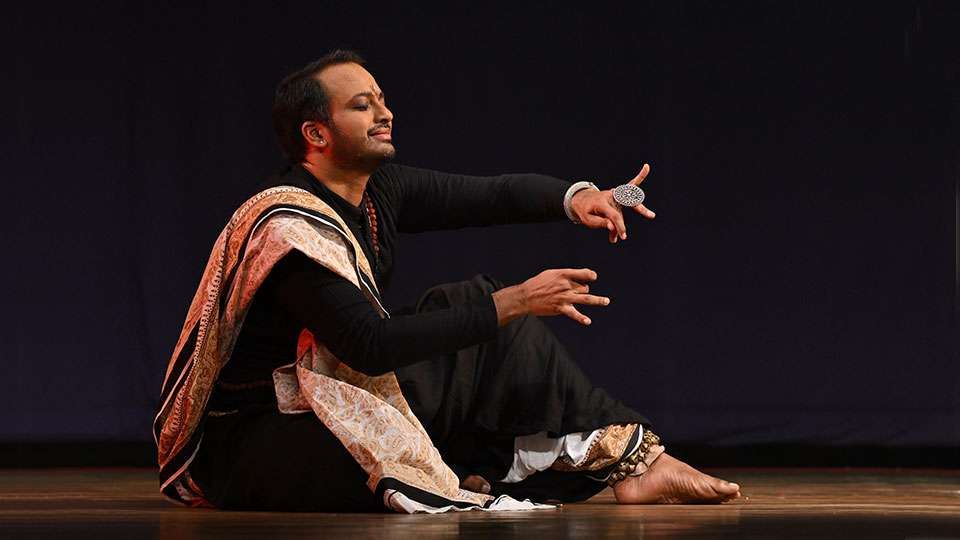

Bhaanak is male-dominated, while Bhaanika is female Dominated.

After the first part, ‘Chitra Purvaranga’ The performers came in a procession with a batavriksha /banyan tree, under which the sutradhara sat.

The work was not smooth-sailing. Piyal Bhattacharya had stumbled upon 8 kinds of Uparupaka or Nritta -Prabhanda or Raga-Kavya from Abhinava Gupta’s commentaries.

The first Scene began with Nirgeeta Vidhi of Chitra Purvaranga of Natyashastra. This Vidhi commenced behind a semi-transparent Curtain or ‘Yavanika’ with the ‘Tri-saam’ playing on ‘Tri-Pushkar’, or the three distinct percussions of Natyashastraic tradition.

In the second scene Asarita-Vardhamana Vidhi, which is typical to Gandharva style of sangeet was shown.

[adrotate group=”9″]

Through the medium of song, dance and dialogue simultaneously the 7 musical notes invoked the seven dimensions of Shiva and seven dimensions of consciousness. The first note invoked Bhairava, the second invoked Ardhanariswara, the third note invoked all the energy centres of the body-the dance of Mahalakshsmi was performed here. The fourth note invoked Shakti in union -energy and matter. The fifth invoked cosmic reflection-Shiva is bimba and the dancer is pratibimba, his reflection and manifestation. The sixth is Kaali-time and the seventh is Maha Saraswati or Tripura Sundari.

The choreography formed a magnificent triangle. Three female performers represented Maha Sarswati, Maha kaali, and Mahalakshmi forming a tribhuja throughout the production, keeping Bharata Muni’s abhinaya with Vak; anga and sattwa.

The centre was occupied by the sutradhara, who sang, spoke, danced, acted as per tradition. The sutradhara sat under that Banyan tree and spoke about the evolution of the ‘Word’ or shabda-brahma and its manifestation in the human body and its expression in music.

In Purvaranga, which commenced the drama, four dancers entered the stage in the four consecutive sections of these songs and danced and enacted the drama according to the Sahitya.

[adrotate group=”9″]

Sapta Kapaal-geetis, performed in Bhaanak established the metaphysical truth divulged with the dialogue of the Sutradhara.

To refurbish the age-old Indian concepts and building a rational and relevant bridge with the contemporary audience, besides the use of Sanskrit, the journey took occasional refuge in local Indian languages to communicate with the spectators, momentarily.

Upa-roopakas cannot be foreseen with the notion of ‘dance-drama’; a mode of consummate artistry, here Nritta and Geet are predominant along with Vachik-abhinaya. ‘Udant’ or the social messages and teachings imparted through its performance is its life. The audience came closer to the actors and experienced rasa.

The storyline of Bhaanak presented on the first day revolved around a messenger going through the winding pathways of Ujjain in Spring season carrying ‘praabhritaka’ -a token of love with him. Muladeva the king of Pataliputra had fallen in love with his beautiful sister-in-law Devasena. Lovestruck Muladeva sent his messenger to Ujjain with a lotus for Devasena, his lover. Samvatsara the messenger’s travails, unfolded to him the improprieties of what he witnessed, about which he critiques sarcastically. When he entered Ujjain, he played the role of the sutradhar and invoked Mahakaal-cosmic time. Having given a gist of the play, he switched back to his former role to being Samvatsara. He used his wit to bring forth the interesting characters that he came in contact in his sojourn, to the audience. Thus he revealed the various facets of the less-discussed issues and the hypocrisy of the society, giving important messages and followed his ‘natadharma’ in doing his duty of entertaining the audience. Usual day to do scenes were commented upon to get through to the audience serious social and psychological issues.

The storyline of Bhaanak presented on the first day revolved around a messenger going through the winding pathways of Ujjain in Spring season carrying ‘praabhritaka’ -a token of love with him. Muladeva the king of Pataliputra had fallen in love with his beautiful sister-in-law Devasena. Lovestruck Muladeva sent his messenger to Ujjain with a lotus for Devasena, his lover. Samvatsara the messenger’s travails, unfolded to him the improprieties of what he witnessed, about which he critiques sarcastically. When he entered Ujjain, he played the role of the sutradhar and invoked Mahakaal-cosmic time. Having given a gist of the play, he switched back to his former role to being Samvatsara. He used his wit to bring forth the interesting characters that he came in contact in his sojourn, to the audience. Thus he revealed the various facets of the less-discussed issues and the hypocrisy of the society, giving important messages and followed his ‘natadharma’ in doing his duty of entertaining the audience. Usual day to do scenes were commented upon to get through to the audience serious social and psychological issues.

Tripitaka referred to ‘Bhaanika’ as a performance by a trained reciter ‘who heard many teachings of the wise ones’. A woman-dominated production, here women delivered ‘Udant’ or spoke of the wisdom concealed within the circle of human life. It said: liberation can be attained if we know ourselves and reflect upon the stages of human life. In this line, the saga of Dash-avatars was chosen to be reflected upon as the stages of human life, from birth to demise, which find elucidation in Vajrayana Buddhism. This idea to shed light on Dashavatars came distilled from Abhinavagupta’s Abhinava-Bharati and Bhoja’s Shringara-Prakash. Flowing through several languages, from Sanskrit to Brajbuli and Bangla Panchali, endeavoured to bring the message closer to the secular spectators. The musical instruments used here, like Kinnari Vina and traditional Shri Khol of Bengal, are from the post-Bharata period and many more Buddhist instruments. Bharat Muni himself opened the door wide by saying: any instrument capable of manifesting the desired Rasa, may be used in Natya.

The Sutradhar of the Team (Bhaanak & Bhaanika) was the very talented Sayak Mitra. Sayak also wrote the script for Bhaanika, while Raksh Das wrote the script of Bhaanak. Joy Dalal was the Pakhawaj player and Abhijit Roy played the classical Rabab.

[adrotate group=”9″]

Natya Kutapa -actors-Pinki, Mondal, Rinki Mondal, Shatabdee Banerjee, Manjira Dey, Shreetama Chowdhury, Amrita Dutta, Ruminti Jana Mondal, Moumita Shakhari, Subhendu Ghosh, Rudra Prasad Roy, Soumodeb Hui, Rishav Chakraborty & Piyal Bhattacharya.

Soumen Chakraborty’s light designs were creative. The one-of-its-kind dresses worn, which had no resemblance with any costumes I have ever seen, was designed by Piyal Bhattacharya and Moumita Sakhhari. The imaginatively designed sets that created an ancient world ambience was by Rishikesh Panchal and Rahul Tari.

It was a wonderful production as I saw, authenticated by Dr. Sandhya Purecha who is also a Natya Sashtra scholar and has been working hard to deconstruct this ancient text. Present to see this was Dr. Rudraprasad Sengupta, who is a name in the world of drama along with others.